Canadian Retailers Are On The Peak Of Utilizing More Robots.

In 2009, Sobeys wound up at a junction. Work expenses were rising, laborers productiveness was melting away and the food merchant realized that it needed to continue building greater distribution centers to suit the developing number of items being sold in its supermarkets.

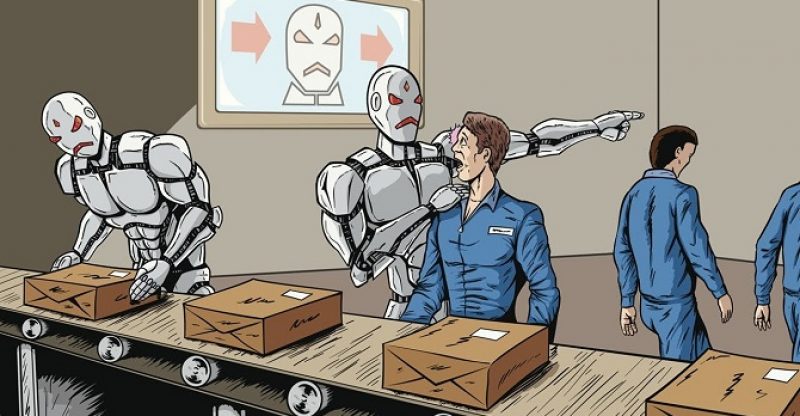

So as opposed to working out and enlisting more laborers, the national grocery chain developed and replace numerous workers with robots.

“The combination of labor costs going up and SKUs (stock keeping units) being on the rise kind of forced us to start thinking outside the box and try to find a technology to help us resolve those issues,” said Eric Seguin, senior vice-president of distribution and logistics for Sobeys, during a tour this week at the company’s largest warehouse in Vaughan, Ont.

Sobeys is one of few Canadian retailers that have grasped mechanical autonomy innovation. Others have been hesitant to take action accordingly, specialists say, because of an absence of investments, an absence of access to the innovation and for quite a while, an absence of competition.

Sobeys today, works four robots distribution centers: two offices north of Toronto spanning 750,000 square feet, another in Montreal and one in Calgary that opened not long ago.

Dissimilar to its 21 customary warehouses, for the most part robotized centers depend on robotics rather than specialized workers to pull things off the racks and pack them onto pallets to ship to its 1,500 or more supermarkets.

Sobeys says the robots, which star here and there lines of stacked items heaped up to 75 feet high for 20 hours per day, have brought about lessened laborers expenses and faster and more precise deliveries. As indicated by Seguin, One robot does the work of four employees.

“The robots don’t get tired,” Seguin said.

“They always show up the morning after the Stanley Cup final. They are always there the morning after the Super Bowl. It doesn’t matter if it’s 35 (Celsius) and a beautiful weekend.”

The company has spent between $100 million to $150 million on each of its mechanical autonomy offices. Seguin says retailers, particularly those in the grocery industry, have been ease back to adjust because of the high forthright investment costs.

“Retail in this country has enjoyed for many decades a bit of a dearth of competition, which is coming to an end now,” said Stephens, who recently wrote a book called Re-Engineering Retail.

According to reports gotten by The Canadian Press in March, government authorities were cautioned that the Canadian economy could lose between 1.5 million and 7.5 million occupations in the following 10 to 15 years because of automation.

In a report, Sunil Johal of the Mowat Center at the University of Toronto estimated that the retail segment utilizes around two million individuals and between 92 percent to 97 percent of the individuals who work in sales or as clerks are at danger of losing their jobs.