World Bank Says By 2050, Drug-Resistant Infections Could Cause Global Economic Damage

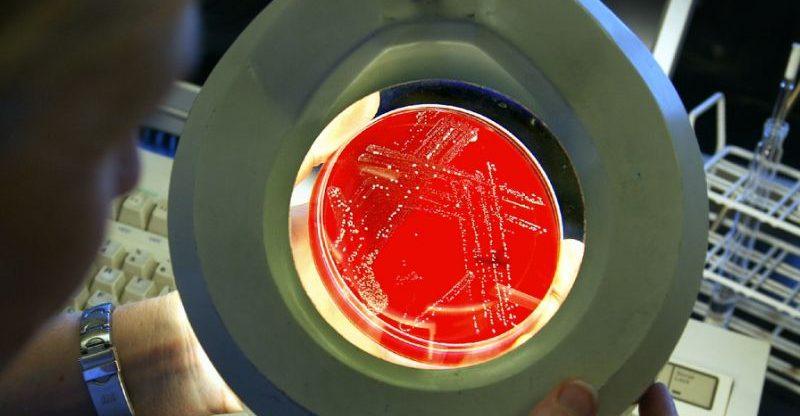

The World Bank has warned that if the drug-resistant infections in people and animals are allowed to spread unchecked, some 28 million people would fall into poverty by 2050. The Bank said in a report released ahead of a high-level meeting on the issue at the United Nations in New York this week, that by 2050, annual global GDP would fall by at least 1.1 percent, although the loss could be as much as 3.8 percent, the equivalent of the 2008 financial crisis.The research shows that a high-case scenario of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), where antibiotics and other antimicrobial dugs no longer treat infections the way they are supposed to, could cause low-income countries to lose more than 5% of their GDP and push up to 28 million people, mostly in developing countries, into poverty.

The research shows that a high-case scenario of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), where antibiotics and other antimicrobial dugs no longer treat infections the way they are supposed to, could cause low-income countries to lose more than 5% of their GDP and push up to 28 million people, mostly in developing countries, into poverty.

“We cannot afford to lose the gains in the last century brought about by the antibiotic era,” Tim Evans, the World Bank’s senior director for health, nutrition and population, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.”By any measure, the cost of inaction on antimicrobial resistance is too great, it needs to be addressed urgently and resolutely,” he said.

“By any measure, the cost of inaction on antimicrobial resistance is too great, it needs to be addressed urgently and resolutely,” he added.

Jim O’Neill, an Economist, noted in another report commissioned by the British Government that greater quantities of antibiotics are used in farming than for treating people. O’Neill said the usage is mostly for promoting animal growth rather than treating sick animals. The O’Neill report estimated that drug-resistant infections could kill more than 10 million people a year by 2050, up from half a million today, and the costs of treatment would soar.Evans said that farmers too would be greatly affected, because it is estimated that by 2050, global livestock production could fall by between 2.6 per cent and 7.5 per cent a year, if the problem of drug resistant super-bugs is not curbed. He said: “Investments are urgently needed to establish basic veterinary public health capacities in developing countries.

Evans said that farmers too would be greatly affected, because it is estimated that by 2050, global livestock production could fall by between 2.6 percent and 7.5 percent a year, if the problem of drug resistant super-bugs is not curbed. He said: “Investments are urgently needed to establish basic veterinary public health capacities in developing countries.

He said: “Investments are urgently needed to establish basic veterinary public health capacities in developing countries.

“Improved disease surveillance, diagnostic laboratories to ensure a disease is identified quickly, inspections of farms and slaughterhouses, training of vets, and oversight over the use of antibiotics are also needed.”The Food and Agriculture Organisation estimated that 60,000 tonnes of antimicrobials are used in livestock each year, a number set to rise with growing demand for animal products.

The Food and Agriculture Organisation estimated that 60,000 tonnes of antimicrobials are used in livestock each year, a number set to rise with growing demand for animal products.

Evans said an investment of some $9 billion a year is needed in veterinary and human health to tackle the issue. He said: “The expected return on this investment is estimated to be between $2 trillion and $5.4 trillion or at least 10 to 20 times the cost, which should help generate political will necessary to make these investments.”Juan Lubroth, Chief Veterinary Officer of FAO, said one of the most important ways to curb the spread of drug resistant microbes in food is to promote good farming practices. Lubroth said: “I think this is where we can do most of our prevention, better knowledge on hygiene, vaccination campaigns, so these animals do not get sick and need antimicrobial drugs.

Juan Lubroth, Chief Veterinary Officer of FAO, said one of the most important ways to curb the spread of drug resistant microbes in food is to promote good farming practices. Lubroth said: “I think this is where we can do most of our prevention, better knowledge on hygiene, vaccination campaigns, so these animals do not get sick and need antimicrobial drugs.

Lubroth stated: “I think this is where we can do most of our prevention, better knowledge on hygiene, vaccination campaigns, so these animals do not get sick and need antimicrobial drugs.

“Public demand for food that is uncontaminated, and better training of health professional’s doctors and vets are also vital to help contain the problem.

“Hospitals and pharmaceutical companies also need to do more to treat their waste.”